If you trust the app, click “Open” to run it. Your Mac will remember this setting for each specific app you allow to run, and you won’t be asked again the next time you run that app. You’ll just have to do this the first time you want to run a new unsigned app. This is the best, most secure way to run a handful of unsigned.

I've been writing a Mac app that runs command-line applications under the hood. This app presents itself as a nice wrapper around a few different image-processing command-line applications: you could download my app and 'free yourself' from having to manage these command-line image processors yourself.

The idea of building a GUI around a command-line app is well-trodden territory: Git clients are a common example.[1] Often, though, these applications assume that you already have the command-line tool installed, and I didn't want to make that assumption with the app I'm building. I wanted some way to embed the command line application in my Mac app so that you could download the app on a fresh computer, on any supported version of MacOS, and be able to use it.

I ultimately figured out how, and will tell you soon, but first...

This isn't a typical way of going about running other dependent programs from your program. If you were building a GUI around Git, for example, you'd likely want to include libgit2—a C library for interacting with Git—as a code dependency, rather than bundling the git command-line executable with your app. If you're processing JPEG images, you'd want to build and use the libjpeg C API instead of building libjpeg and including the jpegtran executable. If you have a library for interacting with the software, you get more natural code hooks for directly interacting with the service, rather than trying to go through a frontend designed for humans.[2] This library will often give you more power and control. It'll be faster, since you won't be spinning up a new process just to run some code. You'll be more easily able to distribute the library, and the library will often work on more targets.[3]

You might not want to work with the whole software library, though, especially if it's designed for more complex use cases than yours. You might be sure you can do everything you want to do from the command-line interface. You might not care about the portability concerns, or the additional time and computing overhead that starting a new process will take. Or there might not be a library for you to work with at all: the command-line interface might be the only way you can interact with the program. If that sounds like your scenario, then carry on.

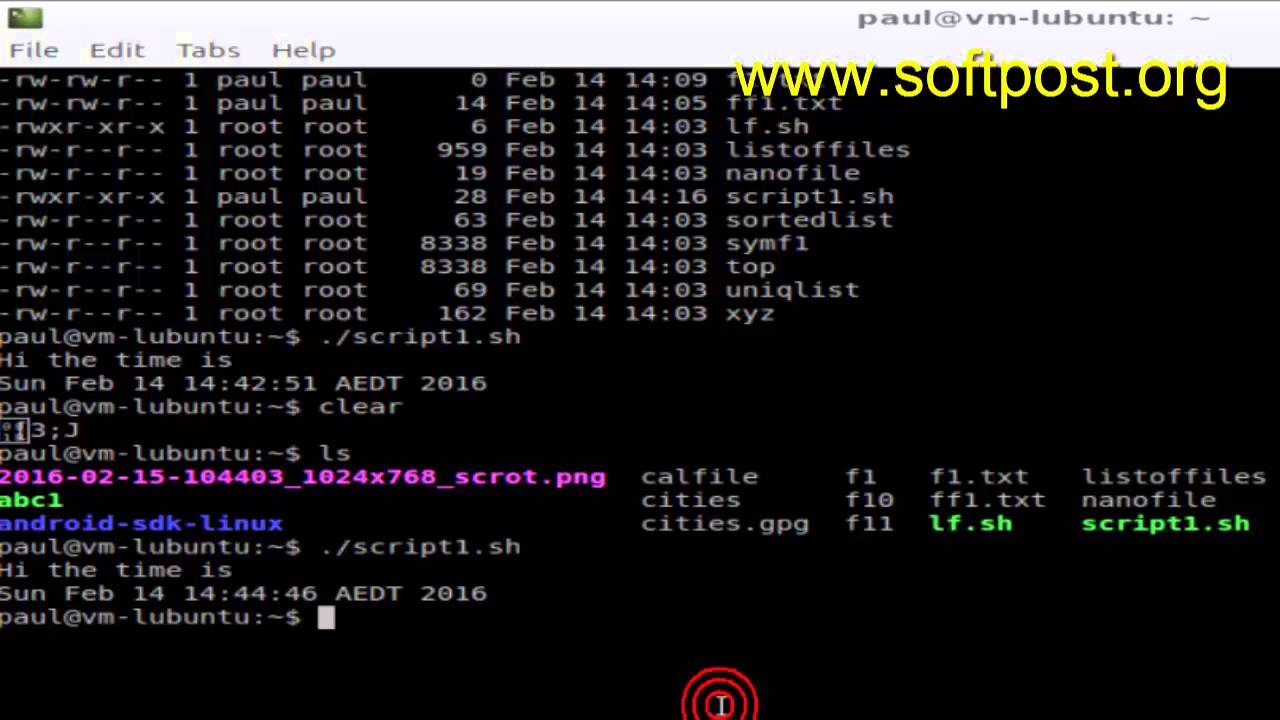

I downloaded the program (in my case, jpegtran) using Homebrew. This installed the compiled executable file (or binary) to my machine. (Alternatively, you could compile jpegtran yourself.) I then located the freshly-installed binary on my disk:

Ultimately, I want to embed this file in my own application bundle[4] and call into it from my code.

I copied the file into my project folder in a special (but arbitrary) directory I had already made. I called it lib, for 'Libraries.'

You'll see a lib folder appear in your Xcode sidebar.

Now, you need to tell Xcode that it should include the lib directory in the application bundle. In Xcode, go to your project settings and click on your application target. In the top navigation bar, you'll see a 'Build Phases' tab, and once you select that tab, you'll see 'Copy Bundle Resources' as one of the build phases. Expand that build phase, and drag and drop the lib directory from Finder into the list of bundle resources.

Now, build and run the app and open the application bundle in the Finder.[5] You'll be able to see your freshly minted lib directory (under Contents/Resources).

Now you can run the command-line app from your code. When you build (and later distribute) your application, the application bundle will have the binary in its lib directory, and you can use Foundation's Process API to run it with all the command-line flags you want:

Unfortunately, though, this probably won't work.

It's highly likely that you're not working with a standalone binary; instead, your binary probably depends on one or more dynamic libraries. Dynamic libraries (sometimes called dylibs) are libraries of code that are installed on the computer in a shared library space, and linked with the executable at runtime.[6] If your binary depends on any dynamic libraries, those dylibs are not guaranteed to be included on the user's system.[7] We have to first include those dylibs in the application bundle, then manually change the command-line app's binary so it will tell the linker to look for those dylibs in the application bundle instead of in the shared library space.

Wait, what?

Binaries contains a list of the names and locations of each dylib that binary depends upon. Those names are set during compilation, so they're accurate for whatever system they're compiled for.[8] You can list the dylibs a given application depends on using otool:

Line In App For Mac

This shows that jpegtran relies on one dylib, and that dylib is located at /usr/lib/libSystem.B.dylib. Your goal for the rest of the article is to patch the jpegtran binary so that instead of pointing in /usr/lib (a location outside the app sandbox), it instead points to the application bundle, where we'll install a copy of the dylib so we can distribute it with our app.

Alright.

To include the dylib in our application bundle, we create a new directory next to lib (I called it frameworks), and copy the dylib into that directory:

Create a new 'Copy Files' build phase and set the destination to 'Frameworks'. Drag your newly-copied dylib from the Finder to the list of files in Xcode. When you build your project, you should see the dylib in Contents/Frameworks.

By installing them into the Frameworks directory, Xcode knows to embed the framework in the application target in such a way that the linker can reference it.

Now that your dylibs will be included (and linkable) whenever you build and distribute your application, you need to point your executable towards the dylib's new home.

Usually, the executable points to an absolute file path. We don't know where the application bundle will live on disk, so we can't use an absolute path here. Fortunately, dyld (the macOS linker) recognizes some keywords that let us build up a relative path instead. For example, @executable_path will be replaced by the path of the binary that requested that dylib. With the install_name_tool utility, we can change the executable so that it points to a dylib path relative to @executable_path. Since the structure of the application binary will always be the same, we can be confident that our relative paths will always resolve.

Starting Mac App From Command Line

As a reminder, here are the relevant files within the application bundle:

We use this command to reconfigure jpegtran to point to a new location for libSystem.B.dylib:

Now, the copy of jpegtran in the lib directory will point to the copy of libSystem.B.dylib in the frameworks directory, and because everything lives in the application bundle, running the command-line application from within your app code won't hit any sandbox-related file access issues, and it won't hit any 'missing dynamic library' issues. If the Swift code to run jpegtran didn't work before, it should work now.

Mac Commands List

This process can be a little tedious. If your binary relies on multiple dylibs, you will have to go through this process for each one. Sometimes, you might encounter a dylib that depends on another dylib. You can use the same tools (otool and install_name_tool) to reconfigure the dylib, just as you did to reconfigure the executable.

Mac Command Line

Yes.

Launch App From Command Line Mac

Of course, we can go one layer deeper. Not only do they make 'GUIs around a command-line app,' people also make and use 'Terminal-based GUIs around a command-line app', like GRV. ↩︎

It's not entirely natural to think of a command-line application as a frontend designed for humans, especially since there are so many tools (like Bash scripts) that programmatically interact with command-line interfaces. ↩︎

A term which here means 'the set of computers, processors, and/or operating systems you want to compile your code to work with.' ↩︎

In macOS, GUI applications aren't just single executable files. Instead, they're bundles: specially handled directories that contain assets, config files, and the executable. ↩︎

Not sure how? Right click on the icon in the dock, and select 'Options → Show in Finder'. Right click on the application in the Finder window, hold down option, and select 'Show Package Contents'. The folder you'll find yourself in holds the contents of the application bundle: welcome! ↩︎

Dynamic libraries are contrasted with static libraries, which are 'burned into' the executable during compilation. When I was talking about libgit2 and libjpeg in the introduction, I was talking about including those static libraries in your application and calling into that code. ↩︎

Even if they were, a sandboxed Mac application can't access files (including dynamic libraries) outside the application bundle unless given specific permission. If you try to call a dylib from within the sandbox, it'll fail. ↩︎

When you install an application from a .pkg file using Installer, one of the things the installer script might be doing is installing new dylibs into your shared library space. ↩︎